Phonological and phonemic awareness skills

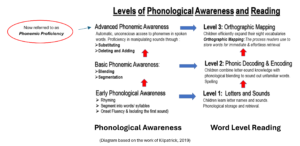

Phonological and phonemic awareness skills have been categorised into 3 levels. Early, Basic, and Advanced.

Before we further discuss the different skill levels of phonological awareness…Let’s clear up some confusion!

In this module we will refer to the work of Dr David Kilpatrick, a professor emeritus of psychology for the State University of New York College at Cortland, who has been teaching courses in learning disabilities and educational psychology since 1994. He is the author of several influential books that have provided evidence-based strategies for improving reading outcomes for struggling readers, is a foundational member of The Reading League, and continues to conduct research into this area of study.

Recently, there has been debate regarding David Kilpatrick’s views on teaching Advanced Phonemic Skills, and Phonemic Proficiency.

The inclusion of Advanced Phonemic Awareness skills, those skills beyond blending and segmenting, in Tier 1 classroom instruction, has been challenged, along with the work of David Kilpatrick who interchangeably used the terms Advanced Phonemic Awareness and Phonemic Proficiency.

Remember this is a normal process in the scientific community, whereby research is questioned and re-examined by colleagues with the aim to building knowledge and testing theories.

The confusion I am referring to, was not the product of Kilpatrick’s hypothesis nor was it what he was teaching, but instead a result of those whom mis understood and miscommunicated his research.

Kilpatrick clarified his position in an interview with Tim Shannahan in 2021, whereby he stated that,

David thought a major clarification was needed. In his 2015 book, he used the terms “phonemic proficiency” and “advanced phonemic awareness” interchangeably to refer to a cognitive or linguistic skill.

He never used these terms to refer to any specific instructional activities. Nevertheless, many educators have conflated advanced phonemic awareness with the notion that certain teaching activities, namely phoneme deletion and substitution, were required. That notion came from some readers of his book, not from David. He never claimed that all kids needed to be engaged in deletion or substitution tasks.

This misunderstanding has led David to abandon the term “advanced phonemic awareness” altogether. He still refers to the underlying ability that all students must develop as phonemic proficiency. When suggesting relevant instructional activities, he describes them specifically (e.g., blending, segmentation, deletion, substitution). The point is to distinguish the ability that students must learn from the instructional activities we use to promote that ability. (Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov. Paragraph 7).

In his blog, Shanahan later discusses Kilpatrick’s insights regarding phonemic proficiency and its connection to the work of Linnea Ehri (2014).

Kilpatrick… ‘begins with Linnea Ehri’s theory of orthographic mapping. That theory “explains how children learn to read words by sight, to spell words from memory, and to acquire vocabulary words from print” (Ehri, 2014, p. 5). Basically, young readers need to develop sufficient knowledge of the letters and phonemes so that printed words and spelling patterns can be connected with phonological representations in the mind. It is these phonemic representations that are the anchors that secure that information in memory.

Readers only briefly and occasionally “sound out” words when they read. That would be too slow and laborious (a fact that troubles balanced literacy proponents). Orthographic mapping, like any kind of fast mapping (the concept was drawn from the language learning literature) is about getting information into memory quickly and effortlessly’. (Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov)

Shannahan explains that Kilpatrick did not see this research as completed and after reviewing a plethora of studies to see why children were not succeeding, he hypothesised that children with core phonological processing deficiencies needed more help developing the phonemic anchors that Ehri (2014) and the National Reading Panel referred to (NICHD, 2000).

‘Meeting typical early learning criteria (e.g., knowing letter names and sounds, segmenting words phonemically) simply were not getting these children far enough….Kilpatrick’s hypothesis is that for most kids, developing PA to the point where they can fully segment words is all that is needed to get things rolling—the PA automaticity that supports orthographic mapping naturally develops from there. He concludes that “business as usual” reading and spelling instruction and reading and writing practice are all that are needed to keep PA proficiency developing. Except…

Except for those kids with core phonological deficits . . . the ones who simply don’t get enough PA support from usual reading experience. They would, he hypothesizes, benefit from more extended PA instruction to promote the phonemic proficiency displayed by typical readers. The point of this isn’t to engage kids in particular kinds of practice (e.g., deleting phonemes, adding phonemes, reversing phonemes), though engaging in some of them may be part of such practice – David thinks that could be beneficial. No, the purpose is to enable orthographic mapping. (Expert form Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov.)

So, to be clear, Kilpatrick’s recommendation was not to systematically teach beyond proficient and automatic application of segmenting and deleting. For most students this is all that is required for ongoing self-teaching and orthographic mapping to develop. His hypothesis is that those that struggled would benefit from further explicit instruction beyond these levels i.e. adding deleting and substitution, for the purpose of orthographic mapping.

Reference Kilpatrick, D. 2015. Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, John Wiley & Sons).

Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov). RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness | Shanahan on Literacy

If you would like, you could always dive deep into the hole of further reading! Here’s a few to get you started.

A-deep-dive-into-phonemic-proficiency_Mar2023.pdf

Phonological Awareness: Instructional and Assessment Guidelines | Reading Rockets

The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read – Keys to Literacy

» Things tie together when you have a really good theory

Phonological awareness (emergent literacy) | vic.gov.au

So now let’s unpack the Phonological Awareness skills further!

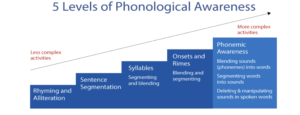

The following continuum illustrates the skills from easier to most complex and illustrates the growing

complexity within each skill. However, acquisition of these skills does not follow a specific order and is varied depending upon the individual student.

The Phonological Awareness Continuum (below left) illustrates the progression of instruction beginning with the larger units of sound(words) to the smallest units of sound (phonemes).

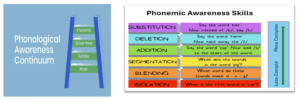

Phonemic Awareness skills (below right) also have a hierarchy of complexity. The diagram illustrates the progression of skills and growing complexity as students work through the phonemic level of instruction. It is now recommended for students to be introduced to working at the phoneme level, as early as possible in Prep /Foundational and Year 1.

Less instructional time focused on early phonological skills, which continue to develop overtime, allows for extended opportunities to practice basic skills that directly support decoding and encoding.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the acquisition of phonological skills and word level reading. Automaticity of the graphophonic connection + phonemic proficiency of blending, segmenting, adding, deleting and substituting, supports the cognitive process of orthographic mapping.

Early Phonological Awareness Skills

- There are three early phonological awareness skills, rhyming, segmenting & blending words/syllables, and onset fluency (alliteration & isolating the first sound).

Basic Phonemic Awareness

At the next level of complexity there are two basic skills: blending and segmenting phonemes.

- Blending has a direct correlation to developing phonic decoding skills for our students. When we say to our students, ‘s’, ‘u’, ‘n’, put it together, what does it say? ‘sun’, Later, when they see ‘s’, ‘u’, ‘n’, in print they use their blending skills to be able to decode the word.

- When a student is writing words, the segmenting skills they are learning aurally enables them to encode the sounds they hear in a word to write the graphemes associated with that word.

- Blending and Segmenting are skills that develop throughout Kindergarten, Prep(foundation) and Grade 1, and are necessary for students to be able to work at the advanced levels of phonemic awareness. It is essential that students have developed phonemic proficiency at this level.

- Research has shown that often, phonemic awareness lessons stop at this basic level. Whilst most students that can blend and segment proficiently will continue to develop beyond this level, students that struggle with reading may need explicit instruction for this to eventuate.

Advanced Phonemic Awareness (Phonemic Proficiency)

At the advanced level there are three skills: adding, deleting, and substituting, phonemes. These skills can develop beyond third and fourth grade.

- These skills help develop students’ ability to manipulate sounds in words which is essential to them becoming an automatic decoder and encoder.

- The ability to be able to cognitively manipulate sounds instantaneously is essential for the process of orthographic mapping and development of a large sight word lexicon.

- Kilpatrick (2019) has hypothesised that children with phonological core deficits, who are struggling with reading and writing may benefit from explicit intervention in this area.

This remains a contentious area of study, and it has been agreed that further research into Kilpatrick’s hypothesis in teaching advanced skills to struggling readers, is required before it can be substantiated.

Sequence of Phonological Skills

Rhyme

- Rhyme recognition

- Rhyme creation

Onset Rime

- Onset fluency/ Isolating the first sound e.g. cat /c/

- Identify the initial sound from a list of words e.g. mum, monster, mango /m/

- Create words with the same beginning sound e.g. dog / dad

Blending

- Word Level

- Syllable level (Build complexity through introducing 1, 2, 3, 4 syllable words),

- Onset Rime

- Phoneme level

Segmenting

- Word Level

- Syllable level (Build complexity through introducing 1, 2, 3, 4 syllable words),

- Onset Rime

- Phoneme level

Manipulating– adding/ deleting / substituting (Phonemic Proficiency)

- Word Level

- Syllable level (Build complexity through introducing 1, 2, 3, 4 syllable words, Affixes)

- Onset Rime

- Phoneme level (Initial, Final and Medial Phonemes, second phoneme in a blend, Digraphs, Trigraphs)

Remember whilst skills may be taught sequentially, acquisition is not sequential, and will develop differently depending upon the child’s experience, language exposure, opportunity to practice, cognitive and physical ability. Research has shown that the most effective instruction combines Phonemic Awareness with Structured Synthetic Phonics followed by regular opportunity to apply their developing knowledge (Brady, 2020, TRL Journal, Vol.1).