Why is phonological awareness important to the developing reader?

‘The lack of phonemic awareness is the MOST powerful determinant of the likelihood of failure to read’. (Adams, 1990)

Phonological awareness skills are critical for learning to read and write any alphabetic writing system. Research has overwhelmingly proven that difficulty with phonemic awareness and other phonological skills is a strong predictor for poor reading and spelling (Adams,1990). Adam’s states that,

“…without direct instructional support, phonemic awareness eludes roughly 25 percent of middle-class first graders and substantially more of those who come from less literacy-rich backgrounds. Furthermore, these children evidence serious difficulty in learning to read and write’ (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998. The Elusive Phoneme, American Educator, Spring Summer Beginning to Read: Thinking and learning about print, American Educator, Spring Summer). The Elusive Phoneme

The research of Hulme, Bowyer-Crane, Carroll, Duff, & Snowling, 2012; Melby-Lervag, Hulme, & Halaas Lyster, 2012; Vellutino et al., 2004, concluded that phonological awareness difficulties represent the most common underlying source of word-level reading difficulties.

David Kilpatrick (2016) found that only 60% to 70% of children would develop phoneme awareness naturally. The gap that Adam’s had referred to had widened to 30-40%. He stated that,

‘…every point in a child’s development of word-level reading is substantially affected by phonological awareness skills, from learning letter names all the way up to efficiently adding new, multi-syllabic words to the sight vocabulary.’

At his 2019 LDA National Tour Seminar, in Melbourne, Kilpatrick referred to the finding of Fletcher, et al. 2007, Aaron, Joshi et al. 2008, whereby it was concluded that approximately 75% to 80% of children with word reading difficulties had a phonological deficit.

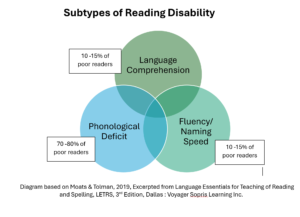

Researchers currently propose that there are three types of developmental reading deficits that often overlap but can also be separate and distinct:

- Phonological deficit, implicating a core problem in the phonological processing system of oral language.

- Processing speed/orthographic processing deficit, affecting speed and accuracy of printed word recognition (also called naming speed problem or fluency problem).

- Comprehension deficit, often coinciding with the first two types of problems, but specifically found in children with social-linguistic disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum), vocabulary weaknesses, generalized language learning disorders, and learning difficulties that affect abstract reasoning and logical thinking.

(Moats, L. & Tolman, C. 2009 Excerpted from Types of Reading Disability, Reading Rockets website). Types of Reading Disability | Reading Rockets

Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2009). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of

Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Challenge of Learning to Read (Module 1). Boston: Sopris West.

Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Challenge of Learning to Read (Module 1). Boston: Sopris West.

When you reflect on this statistic, it translates to roughly a quarter to a third of students from ‘middle class’ backgrounds, who would possibly struggle to develop the necessary phonemic awareness skills required to become proficient readers and writers. Imagine the percentage of students who would struggle to develop these skills that come from a less literacy rich background.

“Every point in a child’s development of word-level reading is substantially affected by phonological awareness skills, from learning letter names all the way up to efficiently adding new, multi-syllabic words to the sight vocabulary.” (Kilpatrick, 2015)

Kilpatrick, states that it is conclusive that phonological and phonemic awareness are especially important at the earliest stages of reading development in kindergarten, pre-school, and first grade students and in addition, phonological awareness continues to develop in typical readers beyond first grade (2012). Research has also proven that a level of phonemic proficiency is required for the cognitive process of orthographic mapping to occur, for efficient sight-word learning (Dixon et al. 2002, Ehri, 2005a; Lang & Hulme, 1999). Readers with phonological processing weaknesses also tend to be the poorest spellers (Cassar, Treiman, Moats, Pollo, & Kessler, 2005).

Thus, explicit instruction of the speech sounds (phonemes) in these early years can accelerate learning the alphabetic code and in turn, alleviate future reading and spelling problems for many students (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998; Gillon, 2004; NICHD, 2000; Rath, 2001). However, struggling decoders of any age can work on phonological / phonemic awareness, especially if they evidence problems in blending or segmenting phonemes (Moats, 2000).

In Module 1 we explored the Reading Brain and the 4 Part Processing Model of Word Reading. The phonological processor mentioned in these models, usually works unconsciously when we listen and speak. Our brains extract the meaning of what is said, not to notice the speech sounds in the words. It is designed to do its job automatically in the service of efficient communication. The difference with reading and spelling is that they require a level of metalinguistic speech that is not natural or easily acquired, thus requiring systematic, cumulative, explicit instruction.

Phonological awareness is critical for learning to read any alphabetic writing system (Ehri, 2004; Rath, 2001; Troia, 2004) and provides the foundation for learning to communicate, using the same writing system.

Phoneme awareness predicts later outcomes in reading and spelling

Research has proven that phoneme awareness facilitates growth in word recognition. Before a student learns to read, researchers have demonstrated that is possible to predict with a high level of accuracy, whether a student will be a good reader or a poor reader by the end of third grade and beyond (Good, Simmons, and Kame’enui, 2001; Torgesen, 1998, 2004). Simple tests that measure phonemic awareness, knowledge of letter names, knowledge of the sound-symbol relationship and vocabulary provide essential information regarding a student’s word reading development.

Instruction in speech-sound awareness reduces and alleviates reading and spelling difficulties (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998; Gillon, 2004; NICHD, 2000; Rath, 2001). Teaching speech sounds explicitly and directly also accelerates learning of the alphabetic code. Therefore, classroom instruction for beginning readers should include phoneme awareness activities.

Phonological and phonemic awareness skills

Phonological and phonemic awareness skills have been categorised into 3 levels. Early, Basic, and Advanced.

Before we further discuss the different skill levels of phonological awareness…Let’s clear up some confusion!

In this module we will refer to the work of Dr David Kilpatrick, a professor emeritus of psychology for the State University of New York College at Cortland, who has been teaching courses in learning disabilities and educational psychology since 1994. He is the author of several influential books that have provided evidence-based strategies for improving reading outcomes for struggling readers, is a foundational member of The Reading League, and continues to conduct research into this area of study.

Recently, there has been debate regarding David Kilpatrick’s views on teaching Advanced Phonemic Skills, and Phonemic Proficiency.

The inclusion of Advanced Phonemic Awareness skills, those skills beyond blending and segmenting, in Tier 1 classroom instruction, has been challenged, along with the work of David Kilpatrick who interchangeably used the terms Advanced Phonemic Awareness and Phonemic Proficiency.

Remember this is a normal process in the scientific community, whereby research is questioned and re-examined by colleagues with the aim to building knowledge and testing theories.

The confusion I am referring to, was not the product of Kilpatrick’s hypothesis nor was it what he was teaching, but instead a result of those whom mis understood and miscommunicated his research.

Kilpatrick clarified his position in an interview with Tim Shannahan in 2021, whereby he stated that,

David thought a major clarification was needed. In his 2015 book, he used the terms “phonemic proficiency” and “advanced phonemic awareness” interchangeably to refer to a cognitive or linguistic skill.

He never used these terms to refer to any specific instructional activities. Nevertheless, many educators have conflated advanced phonemic awareness with the notion that certain teaching activities, namely phoneme deletion and substitution, were required. That notion came from some readers of his book, not from David. He never claimed that all kids needed to be engaged in deletion or substitution tasks.

This misunderstanding has led David to abandon the term “advanced phonemic awareness” altogether. He still refers to the underlying ability that all students must develop as phonemic proficiency. When suggesting relevant instructional activities, he describes them specifically (e.g., blending, segmentation, deletion, substitution). The point is to distinguish the ability that students must learn from the instructional activities we use to promote that ability. (Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov. Paragraph 7).

In his blog, Shanahan later discusses Kilpatrick’s insights regarding phonemic proficiency and its connection to the work of Linnea Ehri (2014).

Kilpatrick… ‘ begins with Linnea Ehri’s theory of orthographic mapping. That theory “explains how children learn to read words by sight, to spell words from memory, and to acquire vocabulary words from print” (Ehri, 2014, p. 5). Basically, young readers need to develop sufficient knowledge of the letters and phonemes so that printed words and spelling patterns can be connected with phonological representations in the mind. It is these phonemic representations that are the anchors that secure that information in memory.

Readers only briefly and occasionally “sound out” words when they read. That would be too slow and laborious (a fact that troubles balanced literacy proponents). Orthographic mapping, like any kind of fast mapping (the concept was drawn from the language learning literature) is about getting information into memory quickly and effortlessly’. (Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov)

Shannahan explains that Kilpatrick did not see this research as completed and after reviewing a plethora of studies to see why children were not succeeding, he hypothesised that children with core phonological processing deficiencies needed more help developing the phonemic anchors that Ehri (2014) and the National Reading Panel referred to (NICHD, 2000).

‘Meeting typical early learning criteria (e.g., knowing letter names and sounds, segmenting words phonemically) simply were not getting these children far enough….Kilpatrick’s hypothesis is that for most kids, developing PA to the point where they can fully segment words is all that is needed to get things rolling—the PA automaticity that supports orthographic mapping naturally develops from there. He concludes that “business as usual” reading and spelling instruction and reading and writing practice are all that are needed to keep PA proficiency developing. Except…

Except for those kids with core phonological deficits . . . the ones who simply don’t get enough PA support from usual reading experience. They would, he hypothesizes, benefit from more extended PA instruction to promote the phonemic proficiency displayed by typical readers. The point of this isn’t to engage kids in particular kinds of practice (e.g., deleting phonemes, adding phonemes, reversing phonemes), though engaging in some of them may be part of such practice – David thinks that could be beneficial. No, the purpose is to enable orthographic mapping. (Expert form Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov.)

So, to be clear, Kilpatrick’s recommendation was not to systematically teach beyond proficient and automatic application of segmenting and deleting. For most students this is all that is required for ongoing self-teaching and orthographic mapping to develop. His hypothesis is that those that struggled would benefit from further explicit instruction beyond these levels i.e. adding deleting and substitution, for the purpose of orthographic mapping.

References

Kilpatrick, D. 2015. Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, John Wiley & Sons)

Shanahan, 2021. RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness. Shanahan on Literacy, 13th Nov). RIP to Advanced Phonemic Awareness | Shanahan on Literacy

If you would like, you could always dive deep into the hole of further reading! Here’s a few to get you started.

A-deep-dive-into-phonemic-proficiency_Mar2023.pdf

Phonological Awareness: Instructional and Assessment Guidelines | Reading Rockets

Why Phonological Awareness Is Important for Reading and Spelling | Reading Rockets

The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read – Keys to Literacy