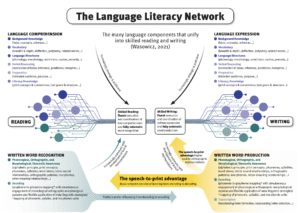

Wasowicz, J. (2021) The Language Literacy Network. Learning By Design, Inc. www.learningbydesign.com

The benefits of connecting reading and writing

“The evidence is clear: writing can be a vehicle for improving reading. In particular, having students write about a text they are reading enhances how well they comprehend it. The same result occurs when students write about a text from different content areas, such as science and social studies.”

Writing to Read: Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Writing and Writing Instruction on Reading. Graham and Herbert, Harvard Educational Review (2011) 81 (4):710-744

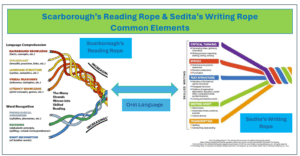

The Language Literacy Network model from the Language Literacy Network from Learning by Design.. illustrates the interconnectedness of reading and writing. It includes Scarborough’s Reading Rope strands alongside the Sedita’s Writing Rope Strands, illustrating the common elements and the symbiotic relationship between the two.

Listen to Joan Sedita author of The Reading & Writing Rope, and Marjorie Bottari from Heggerty discuss the interconnectedness of reading and writing. At 13.00 Dr Sedita specifically focuses on the connection between the two and its impact on comprehension and the impact on long term outcomes.

Series 5: Ep.4- The Reading-Writing Connection with Joan Sedita

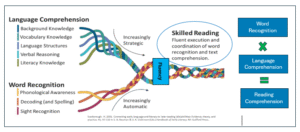

By combining these theories, and identifying the common elements, a more holistic understanding that effective reading and writing involves a complex interplay of cognitive, linguistic, and social-cognitive factors. This integrated approach acknowledges the importance of the:

- Word Recognition and Language Comprehension skills, of the Reading Rope.

- Language Expression and Written Word Production skills of the Writing Rope.

Clarity of their interconnectedness and how they can be combined when planning, along with an understanding of student’s individual experience and background knowledge, allows teachers to plan most effectively for improved student outcomes.

Now Read how Dr Nathaniel Swain approaches building early literacy skills in a multifaceted way that caters to individual needs of students in foundational and early years classrooms.

Cognitorium | Teaching all facets of literacy — Dr Nathaniel Swain

Previously teachers have separated reading and writing components in the literacy block, struggling to cover both effectively. It would seem more effective to consider dividing our instructional time into the lower and upper strands of Network model (above).

The top section of the Network Model (above) focuses on the language features, text structures and the elements of text, whilst the bottom of the network focuses upon the encoding, decoding, and transcription skills.

For students to develop proficiency, they require a level of automaticity of the bottom strands, a product of explicit, sequential and cumulative instruction and repeated practice at word level. In collaboration with syntactic understanding and the automaticity of the transcription skills students can begin to effectively communicate via both pathways.

In the upper primary and early secondary grades, we often assume that the time spent on building automaticity of the foundational skills in the lower years, allows us to focus on developing the top of the network for both reading and writing. This ultimately depends upon the quality Tier 1 instruction in the early years, interventions provided and individual background and experience of each student. Whilst the balance tips in this favour, we must always be aware of elements of the reading and writing ropes, the problems that can occur, how to identify their genesis, and what instructional routines and interventions can support success.

In the lower grades we focus on building knowledge and skills in vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, pragmatics and literacy knowledge though the language comprehension strands, until students become more strategic in their application as they move through each year of schooling. As students become increasingly proficient at the lower foundational skills, they can shift the cognitive load from learning to read/ write to reading/ writing to learn. Concurrently, teachers strategically build background knowledge to help support the development of mental models that support reading and writing.

In summary, reading and writing draw on the same sets of linguistic and other knowledge i.e. alphabetic knowledge, grapheme-phoneme correspondence, grammar, spelling and punctuation, vocabulary, text structure, syntax, background knowledge, and purpose and audience. To capitalise on the interconnection between reading and writing, (and speaking and listening), students need explicit instruction, and multiple opportunities to practice daily.

This can be done effectively if we attend to literacy in all key learning areas, through using a knowledge rich curriculum, and strategically planning a sequential and cumulative whole school scope and sequence.

So how does this work in a classroom?

Ultimately when speaking, listening, reading and writing are integrated in instruction, there is a reciprocity between the elements that leads to improvement in both students’ reading and writing.

For example, teachers may guide their students through the analysis of a text, focusing on structure and meaning-making techniques. Students can then practice retrieving and drawing upon this new knowledge to write about the content that they have read in their text/ knowledge-based units. This process can help build understanding about how texts work, which in turn informs their skills in both reading and writing.

The roles speaking and reading play, in learning to write, is evident when the knowledge that students need to access, when engaged in writing, is considered. To write confidently, students need to have something to ‘say’. They need to have sufficient knowledge of the topic (background knowledge) which they have built through reading and viewing activities, knowledge of literate language, and proficient transcription skills. For example:

- Students and teachers share topic information through read alouds and discussions, record it on graphic organisers, charts, and annotated texts. The collective information is available to all students to draw on when creating texts.

- Reading and deconstructing texts are rich activities and offer opportunities for the development of students’ oral language skills, alongside knowledge of the textual structure and features etc.

- Repeated and close reading, allows students to return to a text as they learn new content, vocabulary and structure. Teachers explicitly teach and help students identify the textual features and elements the author has used in a text (to persuade, inform, entertain etc). This helps build a framework that they can refer to for their own writing.

- Annotated exemplars provide students with knowledge of how language works depending on the subject matter, purpose and audience and the mode of communication. By collaboratively deconstructing a text, students can identify and discuss how the:

- text is organised to achieve its purpose,

- text is structured,

- author makes choices about language or multimodal elements.

Key Considerations of the Symbiotic Relationship

- Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening are interdependent in the process of becoming literate.

- Students need to read proficiently, to be able to communicate their thoughts through writing.

- Reading exposes students to the different text types and structures that they must write.

- Students must read to critically reflect upon a text, before editing and refining their ideas.

Links for further learning

- Dr Steve Graham explaining the Reading Writing Connection (Reading Rockets) https://youtu.be/tA7QU2s8VSQ?si=CHsLDXGCPf9y1PB1

- Steve Graham discusses ways you can help a student with learning difficulties “Teaching Writing to Students with Learning Disabilities https://youtu.be/3elRpGj3zm0?si=kNrGtYddBPzaOoXI

- Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading : Publications | Carnegie Corporation of New York

- The Symbiotic Relationship Between Reading and Writing | Edutopia

- The What, Why and How Long of the Literacy Block

High Yield Instructional Strategies

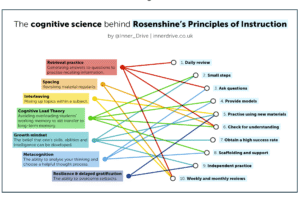

Rosenshein’s Principles

‘Without an understanding of human cognitive architecture, instruction is blind.’

(John Sweller, 2017)

A brief guide to Rosenshine’s 10 Principles of Instruction | InnerDrive

What are Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction?

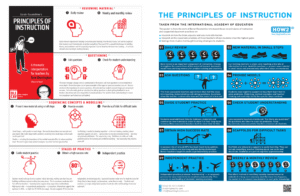

Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction are high yield instructional strategies that are research based and provide a framework for designing and delivering effective lessons that prioritise student mastery of knowledge and improved outcomes.

Key Principles:

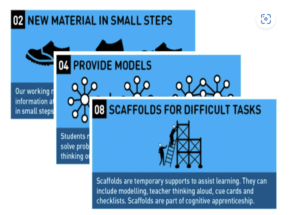

- Present new material using small steps

- Provide models

- Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks

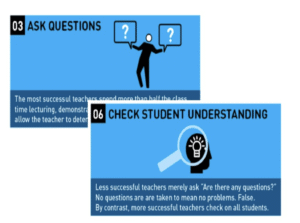

- Ask questions

- Check for student understanding

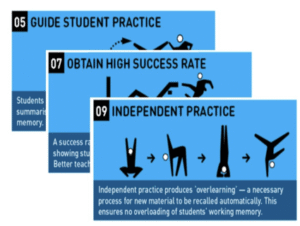

- Guide student practice

- Obtain a high success rate

- Independent practice

- Daily Review

- Weekly and Monthly reviews

Listen to Tom Sherrington author of the “Rosenshein’s Principles in Action” explain Rosenshine’s Principles. INTED2022 – Tom Sherrington talking about Rosenhine’s Principles in Action

https://youtu.be/6NBaLy364u8?si=xhu1WjSmRy0yolB7

Reviewing Material – Daily Review and Weekly & Monthly Review

Daily review provides a deliberately planned opportunity to revisit prior learning from the last lesson. It’s a powerful technique for building fluency and confidence and is especially important if new learning is to be connected to active relevant prior learning in working memory.

Weekly and monthly reviews continue the process of building long-term memory to support future learning.

Revisit and review: Teaching for how students learn (AERO)

This video demonstrates how teachers revisit and review student learning in alignment with AERO’s model of teaching and learning. Revisiting learning is the practice of regularly coming back to content that’s already been taught. Revisiting learning can activate prior knowledge to connect new learning with what students already know (from their previous learning at school, in the community and at home). Importantly, revisiting what’s been taught consolidates new learning.

Questioning

Rosenshine provides great examples of the types of questions teachers can ask. He also reinforces the importance of process questions (how students worked something out) and stressing that asking questions is about getting feedback on how well the material has been taught and about the need to check understanding to ensure that misconceptions are addressed.

Monitor progress: Teaching for how students learn (AERO)

https://youtu.be/U1hseh_2QAM?si=o62XxllY7LGC2hN0

Checks for Understanding (Ochre Education)

https://youtu.be/9EnSYqAh3PQ?si=-hFWO0nQfTJFBhVC

Sequencing Concepts & Modelling

These three principles guide how to sequence and support knowledge building.

- Small steps– new material needs to be broken down into small sequential and cumulative steps with practice at each stage.

- Models – the inclusion of models and worked-examples help reduce cognitive load. We need to give many worked examples

- Scaffolding is required to develop expertise. Cognitive supports are given and gradually withdrawn as confidence and competency develop. The sequential and cumulative nature of instruction is the key.

Scaffold practice: Teaching for how students learn (AERO)

https://youtu.be/F-2dYHXi840?si=wOQaB52V1l5FSmt_

This video demonstrates how teachers scaffold practice in alignment with AERO’s model of teaching and learning. Supports – known as scaffolds – consist of guidance from the teacher and tools and resources the student can use. Scaffolds can be designed during planning (planned scaffolding) or introduced during lessons to respond to learning needs as they arise (contingent scaffolding). Teachers select and use scaffolds to support each phase of the learning process as students retain, consolidate and apply their learning.

Stages of Practice

“Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic” (Rosenshine, 2012)

Effective instruction requires close monitoring of student learning, guided practice, feedback and redirection, whilst ensuring students are building confidence and not making too many errors. A high success rate in questioning and practice is important and that the optimum range of learning is within the 80% rate (95% – 100% the task is too easy, 70% is too low). Through independent and monitored practice, students are provided with the opportunities to apply what they have been taught by themselves.

Vary practice: Teaching for how students learn (AERO)

This video demonstrates how teachers provide varied and spaced opportunities for students to practise their learning in alignment with AERO’s model of teaching and learning. Varying the ways students practise consolidates learning better than repeatedly practising in the same ways. Spacing out practice over time supports long-term retention and fluent recall by helping to manage cognitive load.

Links to further information for your interest

How Rosenshine’s principles support curriculum implementation facilitated by Tom Sherrington

https://youtu.be/8oqT4JKN-Y8?si=Ux6sr4Z4vd0zAATf

A brief guide to Rosenshine’s 10 Principles of Instruction | InnerDrive

Let’s here from Rosenshine himself :

Rosenshine part 1 (Conference 2002) on Vimeo

Rosenshine part 2 (Conference in 2002) on Vimeo

This blog by Mark Enser is a superb example of putting Rosenshine’s principles into practice – in this case, his subject is Geography.

Putting theory into practice | Heathfield Teach Share Blog

High Impact Teaching Strategies

High impact teaching strategies and high-ability Victorian State Government – Dept of ED

Explicit Instruction (Fully Guided Practice) – The path from novice to expert

Why Explicit Instruction?

Review your knowledge of Explicit Instruction by listening to Explicit instruction expert, Dr. Anita Archer, provides the rationale and overview of explicit instruction and its benefit to students

Explicit instruction is a systematic, engaging and success-oriented teaching approach. It involves fully explaining and effectively demonstrating what students need to learn. This approach to instruction accords with what we know about the learning process, and empirical evidence on the most effective teaching practices. Learning new information happens most effectively and efficiently when teaching is clear, systematic and does not leave students to construct or discover knowledge and skills without guidance.

Explicit instruction involves breaking down the content of an area of learning, and providing comprehensive explanations, and step-by-step guidance until students are ready to demonstrate their learning independently.

During explicit instruction teachers sequence the content and provide small chunks of new information. Teachers directly explain to students how to complete a task, why the task is important, and how the task relates to and extends their previous knowledge.

Demonstrations of how to perform tasks or solve problems are provided, often using worked examples. Regular checks for understanding are undertaken to allow teachers to identify and address misconceptions and support students’ learning progress. Progress is facilitated by the gradual release of supports until students demonstrate that they have mastered an area of learning and can extend and apply their learning to increasingly complex and independent tasks. (Edreserach.edu.au, September 2023, p1)

Further Information for your reference

AERO – Explicit instruction optimises learning

Welcome to AERO | Australian Education Research Organisation

VTLM 2.0 – Explicit explanation and modelling | Resource | Arc

Explicit teaching practices involve teachers clearly showing students what to do and how to do it, rather than having students discover or construct information for themselves. Explicit instruction is the path to other forms of instruction as it ensures that foundational knowledge and skills are taught to the Novice learner before they move onto Inquiry learning models and expand their learning from an Expert learner’s perspective. Explicit Instruction acknowledges that learning is a cumulative and systematic process and that students need to master foundational skills before moving onto more complex tasks. Lessons focus on clearly defined objectives that are stated in terms of what students will do, and practice activities are purposefully designed to help students master and retain new skills (National Reading Panel 2000).

Explicit or direct instruction is characterised by:

- Planned and sequenced and cumulative lessons,

- Clear learning intentions and success criteria,

- Clear and detailed instructions and modelling,

- Planned, spaced opportunities to practise new learning

- Retrieval Practice

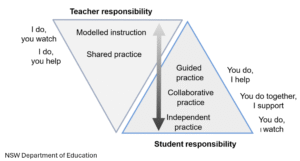

- Gradual release of responsibility (I Do/ We Do/ You Do)

- Frequent, systematic monitoring and feedback

(Rupley, Blair & Nichols 2009 and Archer,2019).

View the Teach explicitly: Teaching for how students learn video from AERO

This video demonstrates how teachers teach explicitly in alignment with AERO’s model of teaching and learning. Introducing new information is most effective when teachers break it down and teach it explicitly using explanation, demonstration and modelling, especially when students are new to that learning area. It involves teaching content explicitly in ways that manage cognitive load to support students with building foundational knowledge before they practise independently.

Resources

Explicit instruction | Australian Education Research Organisation

Explicit instruction optimises learning | Australian Education Research Organisation

AERO – Explicit instruction optimises learning

Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (Fisher& Frey, 2003)

Gradual release of responsibility model – adapted from Fisher and Frey (2003)

In the context of effective reading instruction for the early years, while students are learning the alphabetic code and developing a level of automaticity of the foundational skills (Phonemic Awareness, Phonics and Sight Word Knowledge), the majority of comprehension instruction should focus on oral language comprehension development. Explicit teaching during modelled and shared reading experiences provides students with the opportunity to build language comprehension skills and strategy application. An explicit focus on teaching students to strategically apply their background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, knowledge about texts, understanding of language structures and reasoning skills to texts will support them to develop strong language comprehension abilities as they develop fluent word recognition skills.

Explicit teaching practices involve teachers clearly explaining to students the:

Learning Intention (We are learning to …., This is because ….)

- why they are learning something,

- how it connects to what they already know,

- what they are expected to do.

Success Criteria & Modelled / Annotated Exemplar (You will be successful when….)

- how to do it and what it looks like when they have succeeded.

Explicit teaching provides students with opportunities and time to check their understanding, ask questions and receive clear, effective feedback (Refer to Rosenshine’s Principles)

The Gradual Release of Responsibility Model is a helpful framework to understand what explicit instruction can look like when teaching reading. (Refer to Cognitive Load Theory)

At the heart of the model is the concept that, as we learn new content or skills, the responsibility for the cognitive load shifts from teacher to student. The teacher initially does the heavy lifting, primarily as the model or expert, and the student gradually has the responsibility shift to them as they build confidence in their ability to become independent in the knowledge, skill or concept understanding and the transference and application of this across contexts.

The model is not linear and can be used flexibly rather than from beginning to end. It is a dynamic model that is responsive to the individual and varied demands of students. Instruction can be repeated and revisited as needed and is informed by ongoing formative assessment.

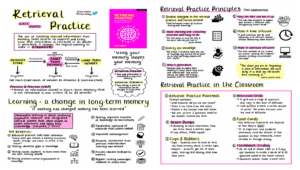

Retrieval Practice and Daily Reviews

Daily review (warm-up, consolidation, ignition) is a deliberate and planned fast-paced retrieval practice of previously learned material. Reviewing material previously taught increases student engagement, builds automaticity and take information from students’ short to long term memory (Rosenshine, 2012).

Retrieval practice reduces the cognitive load by improving the efficiency and accessibility of previously learned information. Our aim as educators is to decrease the extraneous load on our student’s working memory by embedding knowledge into their long-term memory. Every time students have to retrieve information, or generate an answer, the neural connections involved in storing the material is strengthened, making it easier and faster to recall in the future.

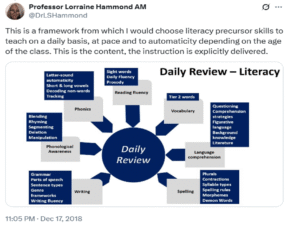

Listen to Professor Lorraine Hammond explain how daily review supports literacy development. Dr Hammond will overview the information processing model and provide guidance to design and deliver daily reviews for reading, spelling, vocabulary and writing that is effective for all students. (Department of Education SA, August 31, 2021)

Below is an image of the Daily Review Literacy framework that Dr Hammond’s uses to guide her choice of skills to teach on a daily basis.

Resources and Daily Review PowerPoints examples

Literacy Hub Daily review example

Phonemes and graphemes daily review

The What, Why and How Long of the Literacy Block

Principles of Instruction – Daily Review AIS NSW Independent Education

The Grammar Project and Daily Review resources

Morkunas-Spaced-interleaved-and-retrieval-practice.pdf

Literacy Block with retrieval Practice SPELD

AERO – Revisit and review: Teaching for how students learn

A little extra for those interested:

Attached is a link to teacher resources created by Grace Hudson @ MissH.biology T&L – Google Drive

Cognitive Overload and Instructional Considerations

Cognitive overload refers to a state where students struggle to process and store new information in memory. Teaching that actively manages cognitive load has a positive impact on students’ ability to engage with learning tasks and retain what they have learned.

Cognitive load theory helps us understand how people learn and store new information, from working memory to long term memory. It provides educators with background information about the cognitive processes involved in learning and how these should be considered when planning explicit instruction to optimise achievement and learning outcomes.

Read the following explainer to understand more about the importance of understanding how cognitive overload impact learning.

Managing cognitive load optimises learning | Australian Education Research Organisation

If you would like to dive deeper in Cognitive Load Theory,

Listen to Dr John Sweller explain Cognitive Load Theory.

Better Thinking #159 – John Sweller on The Cognitive Load Theory

John Sweller – ACE Conference/researchED Melbourne (2017)

Further Links to brief explanations of Cognitive Load Theory and Science of Learning.

Cognitive Load Theory 1 – An introduction

https://youtu.be/KbzmM30NXNQ?si=JPhqf6svOrmyoLLJ

Cognitive Load Theory 2 – Working and Long Term memory

https://youtu.be/ZcoGqi8aiuk?si=Yo926OFDv7TFsW7-

Cognitive Load Theory 3 – intrinsic, extraneous, germane

https://youtu.be/IkH0EGYqWO0?si=n0Oi77_6LXQbAYJQ

Cognitive Load Theory 4 – How to test learning?

https://youtu.be/SWOvuR8sR0Q?si=d7uyfY-gylNxKNTF

Ollie Lovell introduces Cognitive Load Theory

BONUS: Harnessing the Science of Learning with Nathaniel Swain

For further information regarding Cognitive Overload Theory refer to the following links at your will.

Cognitive load theory: Research that teachers really need to understand

Best Education Podcast for Teachers | Ollie Lovell

Structured Literacy (Refer to Module 1)

Structured Literacy is an instructional approach to teach reading that encompasses all of the elements of language. The key principles of Structured Literacy Instruction are that it is:

- Systematic,

- Cumulative,

- Explicit

The International Dyslexia Association came up with this “umbrella term” to unify popular methods, such as Orton Gillingham, Explicit Phonics, and Multisensory Structured Language.

Listen to Nancy Hennessy describe the components of Structured Literacy

Low Variance Curriculum

A “low variance curriculum” refers to a teaching approach that emphasizes consistency and predictability, with a strong focus on a clearly defined scope and sequence. It is a whole school approach that is implemented collaboratively and aims to reduce the variation in instructional practices across classrooms, and year levels, ensuring that students receive a similar learning experience regardless of their teacher or specific classroom. This approach often involves shared instructional routines, explicit instruction, and clear expectations, making it easier for teachers to implement and for students to understand.

Features of a low variance curriculum:

Clear Scope and Sequence:

A low variance curriculum typically has a well-defined scope and sequence, outlining exactly what content will be taught and in what order across the whole school, across each year level and in each classroom. This allows for:

- Continuity of practice between grades means that instruction can pick up where it left off the previous year, with valuable time not being wasted. Assessment and monitoring data can be shared prior to the new year commencing which leaves more time to begin teaching critical content and allows teachers to screen and diagnostically assess students that are new to the school and do not come with evidence that will inform their next steps in learning.

- All students being exposed to the same essential content at the same time, reducing the chance of some students missing important information or learning it out of sequence.

Consistent Routines and Practices:

Low variance curricula often feature consistent routines and predictable instructional practices eg. Daily reviews, Echo reading, Fluency pairs, Repeated Reading, Partner Reading, Connected Phonation etc.

- These routines can include specific lesson structures, questioning strategies, and engagement techniques that are used consistently across classrooms.

- This predictability helps students feel more secure and confident in their learning environment and reduces the cognitive load of learning a new routine.

Explicit Instruction:

A low variance curriculum includes explicit instruction, where teachers break down instruction into smaller achievable chunks before directly teaching the concepts and skills to students. This includes:

- Providing clear learning intentions, success criteria, exemplars, models, and guided practice, allowing students to learn new material in a structured and systematic way.

- The heavy lifting in learning new information and strategies to be gradually released from teacher to student. Transference occurs as skill and knowledge is consolidated through spaced and timed opportunities for practice. (e.g. Anita Archer – Explicit Teaching)

Shared Materials and Resources:

A key component of a low variance approach is often the use of shared materials and resources, such as lesson plans, assessments, and instructional tools. This allows teachers to spend less time on planning and more time on effective instruction, while ensuring that all students have access to high-quality learning materials. There are many high-quality resources now freely available via AERO, OCHRE and ARC to name a few (see links).

Repeated Practice & Focus on Mastery:

Low variance curricula often prioritize mastery learning of foundational skills before moving onto more complex and demanding concepts. It allows students multiple opportunities to practice and consolidate learning until students are able to confidently demonstrate a certain level of proficiency before moving on to new content. Individualised instruction is informed through regular monitoring and feedback, as well as targeted interventions for students who are struggling.

Benefits of a Low Variance Curriculum:

Consistent Learning Experience:

Ensures that all students receive the same quality of instruction, regardless of their classroom.

Clear Expectations & Greater Equity:

A low variance curriculum provides a clear framework for teachers and students, making it easier to understand what is expected of them.

It can help bridge the achievement gap by providing a consistent and known knowledge base that is built over time. Foundational skills are learnt before they are expanded upon in later year levels.

As students move through school, year by year, they are constructing a knowledge base that is known. Teachers have clarity of what has been taught and what will be taught in subsequent years.

Reduced Planning Burden:

Frees up teachers’ time for more effective instruction and individualised support for students.

Improved Student Outcomes:

Research suggests that low variance curricula can lead to improved student achievement and learning gains (Hansberry, 2021). Schools that teach Reading and Spelling in a Research Informed way: Picking a Winner

Strong Instructional Culture:

Creates a shared understanding of what effective instruction looks like within a school – Collective Efficacy.

Want to know more about Low Variance Curriculums?

Here are some links to further information and resources:

Read Building a Coherent Curriculum by Reid Smith — Think Forward Educators

Access Webinar via link Reid Smith – Building a Coherent Curriculum — Think Forward Educators

In this webinar, Reid shares his experiences in working towards a coherent and knowledge-rich curriculum. As part of the session, he discusses the development of a low-variance approach to instruction and its importance to long-term knowledge building

- Building a Coherent Curriculum by Reid Smith | failthinklearn

- Designing a Low Variance Spelling & Reading Curriculum: Jenny Baker FAQs — Think Forward Educators

- Building a Coherent Curriculum by Reid Smith | failthinklearn (Reid Smith)

- S4 Ep19 – Summer Series – High Engagement in Low Variance Instruction Jocelyn Seamer Education

- Schools that teach Reading and Spelling in a Research Informed way: Picking a Winner

- How to implement a whole-school curriculum approach: A guide for principals

- Schools that teach Reading and Spelling in a Research Informed way: Picking a Winner

- In My Classroom: Rebecca Barrett’s Approach to Literacy Intervention | Spellcaster

- Five From Five – NEW series of videos out from Australian… | Facebook

- AERO Teaching for how students learn: Videos of practice | Australian Education Research Organisation

- Low Variance Curriculum Archives – CECG Catalyst

Knowledge Rich Curriculum

A knowledge-based curriculum prioritizes the explicit teaching and retention of subject-specific knowledge and skills, aiming to build a strong foundation of understanding across various subjects or disciplines. It prioritises explicit instruction of the essential knowledge and skills across each stage of schooling and its practice is informed by the ‘Science of Learning’ and principle of effective instruction.

Listen to Dylan Wiliam share his ideas on what a knowledge-rich curriculum is and why it is important for schools.

What is a knowledge-rich curriculum? Teachappy meets Dylan Wiliam

Key Features and Benefits of a Knowledge-Based Curriculum

Subject/ Content-Specific Knowledge: Focuses on disciplinary knowledge within subjects like history, literature, mathematics, and the arts.

Expert-Novice Distinction: Knowledge-based learning recognizes that experts rely on their knowledge base to solve problems, rather than solely on skills.

Explicit Instruction: Direct teaching of the essential knowledge and skills, clearly outlining what students should learn and the skills they should develop.

Stronger Foundations: A knowledge-rich curriculum provides a solid foundation for future learning and understanding.

Sequenced & Cumulative Learning: Organizes knowledge in a way that builds upon prior learning, creating a coherent progression ie Scope & Sequence.

Support Literacy & Reading Comprehension: A knowledge-based curriculum supports literacy development and reading comprehension by building language competence and deep knowledge, enabling students to understand complex subject texts.

Memorization and Retrieval: Emphasizes the importance of actively recalling and remembering learned material by engaging in strategies that strengthen the neural pathways between working memory and long-term memory eg. Retrieval Practice, Daily Review. Thus, ensuring students remember learned concepts, knowledge and skills over time, fostering deeper understanding.

Deeper Understanding: Students develop a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of subjects, moving beyond surface-level knowledge by developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills. They learn to build mental models that enable them to make connections to background knowledge and allow for deeper learning.

Social Equity: By ensuring all students regardless of background, circumstances, or socio-economic status, have access to essential knowledge, a knowledge-rich curriculum can help narrow the achievement gap.

Example of Knowledge Rich Instruction

Organise knowledge: Teaching for how students learn (AERO)

This video demonstrates how teachers can support students to organise their knowledge, aligning with AERO’s model of teaching and learning. When students have opportunities to organise and re-organise their knowledge in memory and understand the connections between the ideas they learn about, they develop mental models in long-term memory that become easier to recall and apply widely in increasingly complex ways.

Want to know more about Knowledge Rich Curriculums?

Here are some links to further information and resources:

- Building a Coherent Curriculum by Reid Smith — Think Forward Educators

- read2Learn — Think Forward Educators

- Podcast S2|E5: Creating a Knowledge Rich Curriculum with Reid Smith – CECG Catalyst

- https://www.podbean.com/ep/pb-dc26z-169cccf

- Full article: The Role of Background Knowledge in Reading Comprehension: A Critical Review

- A knowledge-rich approach to curriculum design: Commissioned report | Australian Education Research Organisation

- AERO – A knowledge-rich approach to curriculum design

- Knowledge rich curriculum meets bulletproof instruction — Dr Nathaniel Swain

- Does Core Knowledge Work Does core knowledge work? | Filling the pail

Curriculum Evaluation Tools

When reviewing curricula for Tier I instruction, it is essential to evaluate programs and resources that you plan to use. It is important that instructional practices are aligned with research and evidence of how children learn to read.

The Reading League has created a Curriculum Evaluation Guidelines which were designed to highlight any non-aligned practices, or “red flags,” that may be present in the areas

Curriculum Evaluation Guidelines – The Reading League