Let’s have a look at the data about literacy in Australia.

Not because we want to beat you up any more than mainstream media has already done but because if we are going to talk about a moral imperative for excellent literacy instruction, there is no better place to start than with understanding where our students are at.

We have all seen the headlines but here are the facts!

As you will know The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an international comparative study of student performance directed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA measures the cumulative outcomes of education by assessing how well 15-year-olds, who are nearing the end of their compulsory schooling in most participating educational systems, are prepared to use the knowledge and skills in particular areas to meet real-life opportunities and challenges.

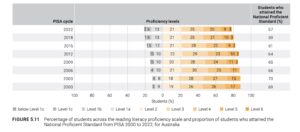

These are the 2022 PISA literacy performance results for Australian children. We are not going to look at the country comparisons because league tables are not particularly helpful. We will focus on the proficiency of our own students only.

The first graph shows the consistent decline for Australian students across the 22 years of testing. And if you look at the graph directly below, you will see that over time, not just does the percentage of students meeting the National proficient standard drop, but we are seeing an increasing number of students in the bottom (darker) proficiency levels and a corresponding lower number of students in the higher (lighter) proficiency levels.

(De Bortoli et al. 2023 p176)

In Queensland, whilst there has been an ongoing decline in results, female students have consistently outperformed males however the 2022 data show a concerning decline in their results.

The story is even bleaker when we consider our more vulnerable students such as our indigenous students, EAL/D students and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

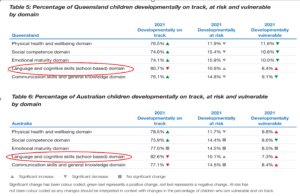

Additionally, the 2021 AECD (Australian Early Development Census) indicates that 19.3% of Queensland children enter school either at risk or vulnerable in the language category of this census (Australian Government, 2021).

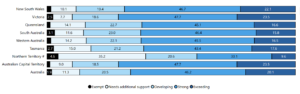

NAPLAN results for reading, 2024

Year 3

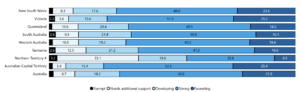

Year 5

The 2024 NAPLAN results in reading show that approximately one third of Year 3 students are not performing proficiently. Students in Year 5 are not significantly closing the gap; in fact, they do not fare much better. (ACARA, 2024 NAPLAN. NAPLAN: National assessment program. Retrieved from NAPLAN National Results).

The impact of this for society is catastrophic.

The impact of illiteracy on the children in our classrooms is seen everyday by every teacher,

- Disengagement in learning and associated behavioural problems,

- Inability to access the curriculum at year level, in all key learning areas (KLA’s),

- Disproportionate number of students with literacy deficits from students that come from I/EALD, EALD, ESL, and lower socio-economic backgrounds,

- Early drop out from school,

- Decreased opportunity to engage in further education/ university,

- Decreased employment and opportunity to build one’s financial security,

- School to prison/ detention pipeline with 85% of first offenders and 90% of repeat offenders being functionally illiterate.

Lower literacy rates have been shown to be associated with increased likelihood of incarceration, poor health, increased unemployment and lower life expectancy.

The data is clearly showing us that something is not working for our students in the literacy space, and this has wide ranging impacts for our society. As educators, it would be irresponsible of us not to at least consider this idea. What we need to do is look at these facts and then turn to the Science of Reading to give us insight on what has been empirically proven to work.

In 2020, Australia’s Jenifer Buckingham published an article ‘Six Reason’s to Use the Science of Reading in Schools’ in the 1st Reading League Journal (Buckingham, J. 2020, Vol 1 Page 15). In that, she shared the results of a review of Australian undergraduate teaching courses, and exposed that,

- only 6% mentioned the 5 essential elements of reading (The 5 Pillars) in the course outline,

- 70% of universities did not refer to them,

- and no outlines referred to the Simple View of Reading (SOR) but referred to other models or theories that had been disproven as ineffective and not supported by research. (Buckingham & Meeks, 2019)

She went on to state that preservice teachers were not being exposed to the research, training and evidence based pedagogical practices required to successfully teach all students to read (Buckingham, J. 2020, p.16).

In 2020 the Australian functional illiteracy rate was reported to be at an all-time low of approximately 44%. This meant that 44% of Australians lacked the literacy skills required to cope with the complex demands of modern life and could not read at a level that society expects. Only 5-10% of these would be categorised as having a language disability. The urgency to change what was happening in our schools, universities and the funding required to meet these demands was and continues to remain very real (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

As a result of the efforts of Buckingham (then Macquarie University NSW), Pam Snow (La Trobe University Vic), Lorraine Hammond (Edith Cowen University WA), Lyn Stone (Life Long Literacy), to name a few, along with recommendations of many educators, ACARA and the Education Minister were provided with crucial evidence that supported changes to the Australian Curriculum.

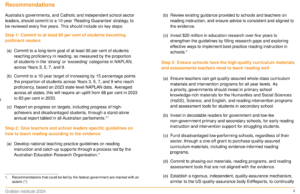

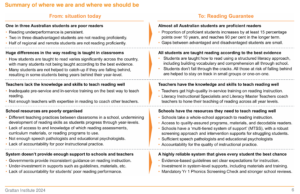

In 2024 the Grattan Institute released their report The Reading Guarantee and made recommendations to address Australia’s literacy crisis. They reported that in a classroom of 24 students, eight would struggle to read. (The Grattan Institute, 2024).

Please read pages 4 to 6

The Reading Guarantee: How to give every child the best chance of success

As an outcome of the advocacy of many educators and the release of the Grattan Report, changes have been mandated throughout Australia, with State Education Departments reassessing their policies and views on how to teach reading, and what professional learning educators required to improve literacy outcomes for all students. Universities have also been required to align the content of their teaching courses with current research-based evidence.

Links to Australian Resources:

Queensland’s reading commitment (QLD)

Reading Position statement (QLD)

Literacy and numeracy guides (NSW)

Teaching reading and phonics | Academy (VIC)

Arc: Supporting Victorian teachers | Department of Education

Further Reading

Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science 2020 moats.pdf